A bus used for the Hajj from Dagestan in the 1990s and early 2000s in the village of Khushtada (Dagestan, Russia), 2024

People and things between Makkah and Dagestan (2022-2024)

Collaborative work with researcher Nastya Indrikova In 2022, we began to search for and collect items that Dagestani pilgrims brought back from the Hajj in the early 1990s: an eclectic mix of commercial goods, detached from religious intentions, alongside cherished souvenirs. The years following the Soviet Union’s collapse became an era of open borders — both cultural and material. Among the throngs of people experiencing the world beyond their borders for the first time were these pilgrims. For them, the Hajj was not only their first trip to Makkah but also their first journey abroad in general. The artefacts they returned with are more than mere objects. They are embodiments of their owners' hopes and dreams and simultaneously tangible links to a shared spiritual heritage that offer an insight into a unique cultural context. In 2023 we were able to add new layers to the story weaving in the threads of pilgrims’ family histories and delving into the intricacies of Hajj’s infrastructure and its attendant commodity exchange networks. Our work in Dagestan, Turkiye and Saudi Arabia revealed a complex ecosystem of trade and exchange, where items carried away from home for sale or brought back from the pilgrimage often helped pilgrims to recoup the cost of the trip, to buy something for themselves with the proceeds, or simply to make money. This project pieces together the pilgrimage paths of Dagestani Muslims tread by multiple generations of a single family and articulates how such intimate experience can be explored through even the most mass-produced, seemingly soulless objects. Pursuing this route ourselves we meld academic inquiry, journalistic investigation, and artistic reflection. Grounded in social anthropology and photography, our approach blurs the boundaries between documentary, museum exhibit, and art, aiming to encapsulate the essence of these pilgrimages and the indelible marks they leave on personal and collective histories. The project was supported by V-A-C Foundation Grant for Artists and Researchers (2022–2023). Exhibited as part of the 'Masaha: Cycle 5' residency at Misk Art Institute (Riyadh, KSA, 2023) and 'Split Together, Merged Apart' exhibition at GES-2 House of Culture (Moscow, Russia, 2025)

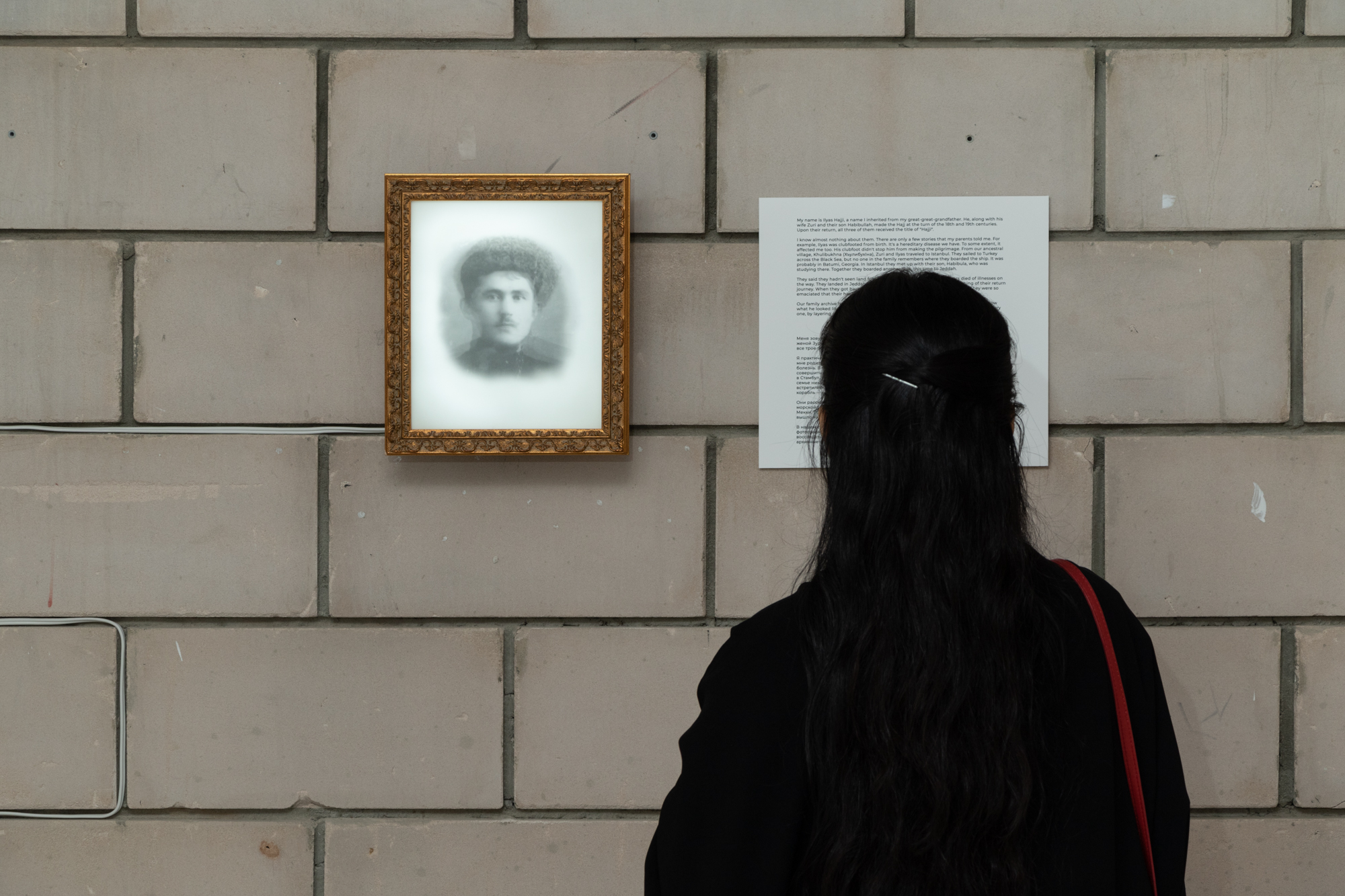

'Split Together, Merged Apart' exhibition. Moscow, 2025. Photo: Daniel Annenkov © GES-2 House of Culture

'Split Together, Merged Apart' exhibition. Moscow, 2025. Photo: Daniel Annenkov © GES-2 House of Culture

'Masaha: Cycle 5' artist residency final showcase. Riyadh, 2023. Photo: Ilyas Hajji

'Masaha: Cycle 5' artist residency final showcase. Riyadh, 2023. Photo: Ilyas Hajji

'Masaha: Cycle 5' artist residency final showcase. Riyadh, 2023. Photo: Ilyas Hajji

Formula of the oneness of Allah on a stone at the entrance to the village of Kulibukhna (Dagestan, Russia), 2022

View of Haydarpaşa Port from Kadıköy district in Istanbul (Turkey), 2023

Caravanserai in Fatih district in Istanbul (Turkey), 2023

Islamic Port of Jeddah from the Central Fish Market (Saudi Arabia), 2023

The restored Eastern Gate of Jeddah from which caravans left for Makkah (Saudi Arabia), 2023

Apartment for pilgrims in Ar Rawabi neighbourhood, Makkah (Saudi Arabia), 2023

Entrance to a pilgrim hotel in the Kuday suburb of Makkah (Saudi Arabia), 2023

The Royal Clock Tower in Makkah (Saudi Arabia), 2023

Pilgrims in Kuday, a suburb of Makkah (Saudi Arabia), 2023

Alarm clock. Purchased in Istanbul (Turkey), 2022

My grandmother Khadijat was the first in our family to make the Hajj after the сollapse of the USSR. She made the pilgrimage to Makkah twice: in 1993 for herself and then in 1996 for her son, who died of leukaemia at the age of twenty. She brought back souvenirs including several plastic alarm clocks in the shape of a mosque that played the adhan at the press of a button. She gave one of the clocks to the imam of our village mosque. He was so impressed by the muezzin’s voice that he sometimes switched it on at the mosque’s microphone when it was time for the Adhan.Ilyas Hajji

The Adhan on the clock was recorded by Abdel Basit Abd us-Samad (1927–1988), an Egyptian hafiz and reciter of the Quran. Tens of thousands of these clocks have been produced. They are familiar to Muslims all over the world and feature in hundreds of videos on the internet with comments from people for whom this Adhan is a childhood memory. The original clock has not survived in the family, but we found an identical one in the Fatih district of Istanbul.Nastya Indrikova

Prayer beads. Brought back from the Hajj in the early twentieth century

My great-grandfather went on the Hajj before the revolution. He went with my great-grandmother to Turkey, picked up their son who was studying at the Islamic University, and from there they travelled by ship via the Red Sea to Jeddah. They went from Jeddah to Makkah in a camel caravan. That’s how they told it. The metal pieces in the rosary are silver carnations.Osman Ilyasov

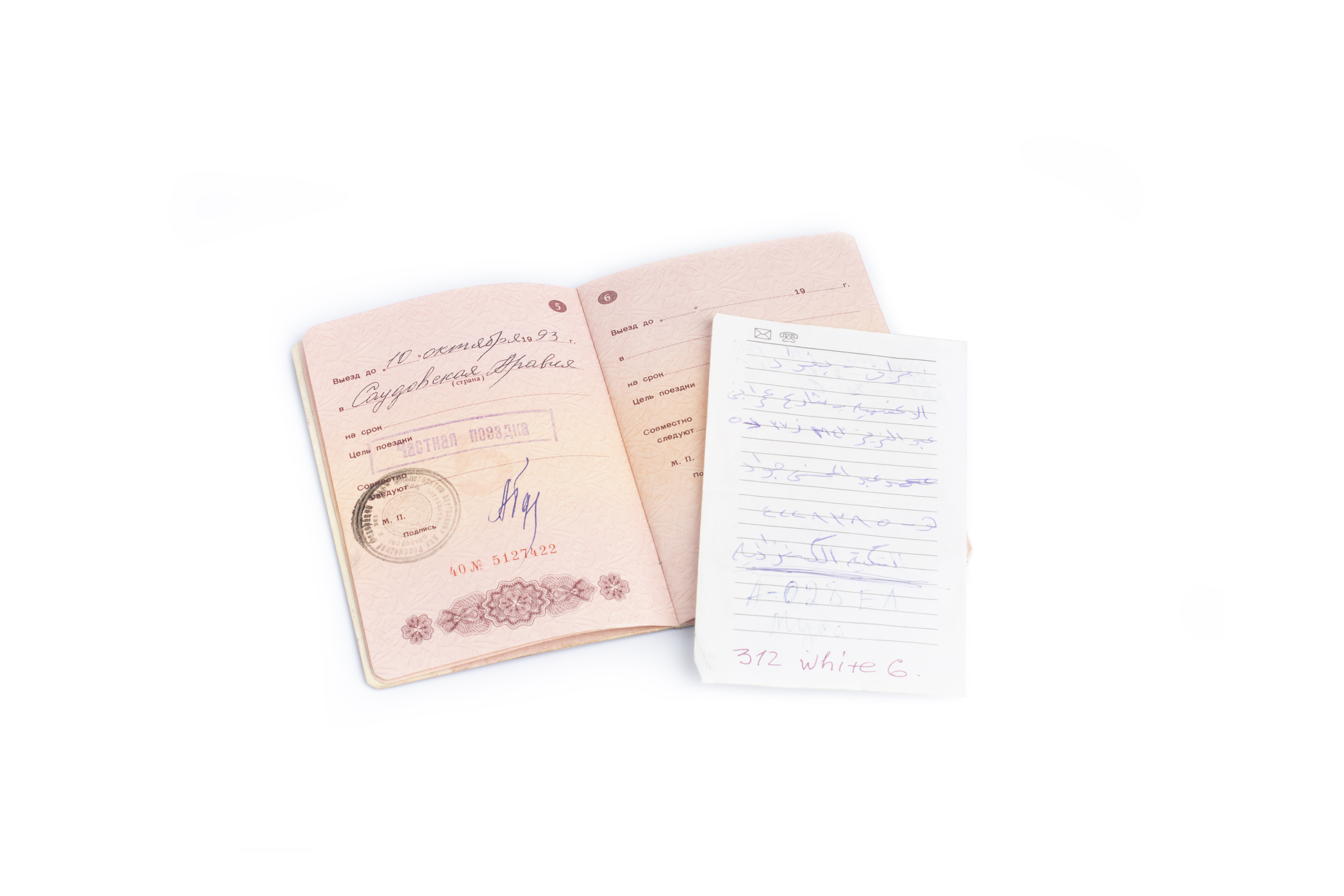

Soviet passport with a Saudi Arabian visa for 1993

I got my visa in 1993, but I didn’t go and only just got my mother and aunt on the plane. There was a swindler who sold a bunch of tickets that year and a lot of people weren’t able to travel. There was a crowd of people outside the airport, but they wouldn’t let anyone in. It was madness! A colonel of the Ministry of Internal Affairs was standing nearby, and I heard him talking to someone in Dargin. I went up and asked him to let my mother and aunt through. He guided them through the crowd. They went and I stayed behind. I had a visa, but I couldn’t fly myself. There were a lot of people looking for that swindler. My mother went on the Hajj twice, the second time on a bus with the father of the first Mufti of Dagestan, Sayidmukhammad Abubakarov. I went on the Hajj a few years before the war in Iraq, in 2002. We went via Azerbaijan, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. It was the shortest route but it took about a week. On the way, we lived in our bus. The first two rows had four benches, and we removed the rest. We put plywood over the remaining metal fixings and made sleeping places. There were no seats, but people who wanted to sit leaned against the windows. Those who wanted to could go and sit on one of the benches when it was free. The driver of our Ikarus bus, an Avar from Khasavyurt, was making the trip for the ninth or tenth time. He was like a tour guide, showing us everything in Madinah, in Baghdad — all the way.Osman Ilyasov

Fluorescent lamp. Purchased in Jeddah (Saudi Arabia), 2002

My father brought back eight lamps like this from the Hajj: one of them he gave to his brother, one to his sister, one to his aunt, one to his brother-in-law, and four he kept for himself. At that time, you couldn’t buy anything like this in our country. The lamp worked from the mains or from a built-in battery. For as long as I can remember, there have been regular power cuts in Makhachkala. For about ten years, we used these lamps when there was a blackout, until the battery finally died. Now I have replaced the fluorescent bulb on one of them with LED strips. I used it for lighting when I first opened a photo studio and I plan to do the same with the others.Ilyas Hajji

Bag. Received as gift in Istanbul (Turkey), 2019

My husband Gadzhi was in Istanbul for work and made friends with some locals. The Turks were planning to make an Umrah and asked if he wanted to go with them. He had never been on either Hajj or Umrah and was keen to go. His Turkish friends paid for him to go with them as a gift. They made the trip with a Turkish travel agency, which gave these bags to all the pilgrims. There were two of them: one large and the other (this one) small. Umar, our eldest son, now uses the small one when he goes to Islamic school. Gadzhi carried his belongings in them when he was in Makkah. My son’s previous school bag ripped, from having too many books in it. So I bought another school bag for him, which now contains textbooks on secular subjects, and gave him this bag for textbooks on Islamic subjects. He attends a private school, founded by Dagestanis, which teaches both regular school subjects and religious subjects.Malikat Ilyasova

A keychain with an image of the Kaaba and the Prophet’s Mosque in Madinah. Purchased in Madinah (Saudi Arabia), 2002

We arrived in Madinah, stayed there for five or six days and when it was time for the Hajj, we moved on. We went to the mosque, did namaz (daily prayer) and then walked around the city. In Madinah, there was a bazaar and many shops. The market was covered, with rows like an arcade. They sold all kinds of souvenirs there. We communicated using a calculator. We asked the seller how much, and he wrote the price on the calculator. I said, “No, that’s too much, let’s make it this much” and wrote another price. That’s how we bargained. The bus was cramped, but it was cheap — the fare was lower because there were more people travelling. In other buses there were five or six less people, but it was more expensive. There were thirty of us, men and women mixed. The sleeping area in the bus was separated by a curtain. We lay down with our heads towards the window, feet towards the middle. There were two connected places between the curtains, so husband and wife slept on opposite sides. We had two couples like that. The women used the back door, we used the front door. All the pilgrims were from Dagestan. Most of them were Avars from Botlikh district, but there were four or five other nationalities as well.Osman Ilyasov